This article is from Goldmine Magazine (Vol. 20 No. 9 Issue 359 dated April 29, 1994). Bruce Ansley contacted Krause Publications Group, Inc. and Dawn Eden and they were kind enough to grant him permission to place the article online. Once he had permission, Bruce transcribed the article and converted it to HTML. This excellent article is reproduced below thanks to Bruce's efforts and the kindness of Krause Publications Group, Inc. and Dawn Eden. The hyperlinks, footnotes, and images have been added by NilssonSchmilsson.com.

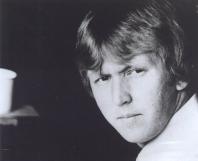

Early RCA Promotional Photograph

Harry Nilsson, as any fan knows, loved the movies. In life, he could do a credible Stan Laurel. In death, he cannot help but be Orson Welles's Citizen Kane. It seems as though everyone who had contact with Nilsson, however fleeting, has a story to tell, and each story only adds to his mystery. Considered one of rock's most literate songwriters, Nilsson had only a ninth-grade education and denied that he was any great reader. A man whose supposed party exploits fed rumor mills for years, he struck close observers as just what both he and his friend John Lennon claimed to be: a pussycat. He alienated some adults with his occasionally foul-mouthed lyrics, yet he won the hearts of kids and kids-at-heart with his sweetly innocent concept album The Point!. Finally, despite the fact that he offered no apologies for his past behavior (including his year long "lost weekend" with Lennon), he was, in his later years, the model of a devoted family man. His life would not be more difficult to analyze if his last word was "Rosebud."

Early RCA Promotional Photograph

Harry Nilsson, as any fan knows, loved the movies. In life, he could do a credible Stan Laurel. In death, he cannot help but be Orson Welles's Citizen Kane. It seems as though everyone who had contact with Nilsson, however fleeting, has a story to tell, and each story only adds to his mystery. Considered one of rock's most literate songwriters, Nilsson had only a ninth-grade education and denied that he was any great reader. A man whose supposed party exploits fed rumor mills for years, he struck close observers as just what both he and his friend John Lennon claimed to be: a pussycat. He alienated some adults with his occasionally foul-mouthed lyrics, yet he won the hearts of kids and kids-at-heart with his sweetly innocent concept album The Point!. Finally, despite the fact that he offered no apologies for his past behavior (including his year long "lost weekend" with Lennon), he was, in his later years, the model of a devoted family man. His life would not be more difficult to analyze if his last word was "Rosebud."

When Goldmine last caught up with Nilsson, on January 7, 1994, the singer was trying as hard as he could to camouflage his flagging health. Although Nilsson's words made it clear that he was, as he put it, "not long for this world," physically and spiritually he projected an image of resolute strength. It was a shock to many, not least of all this writer, when he died only eight days later.

Nilsson's first words into Goldmine's tape recorder were a lengthy quote from his favorite article about himself: Derek Taylor's liner notes to Nilsson's 1968 album Aerial Ballet. Although the notes included the famous statements, "Nilsson is the best contemporary soloist in the world. He is It. He is the something else The Beatles are. He is The One" (words which would be mere hyperbole were they not this side of "true"), Nilsson quoted instead from the opening of the essay:

Slanted-patterned parking lot and the children in the cars of many colors were whining 'Why' and 'When' and stout and bouncing bobbing frozen-food-faced ladies in wobble-pink capris were roller-curling their basket-way to the fat and hungry Riviera trunks and we, store-sullen men, waited in the scorching smog-stained sun on various vinyl-shining seats when I button-pushed into a 17-bar song-snatch and Timothy, eight and bright, said, 'Oh, you're smiling now, why? Oh why? Why ... the song had said: 'He met a girl the kind of girl he'd wanted all his life. She was soft and kind and good to him and he took her for his wife. They got a house not far from town and in a little while the girl had seen the doctor and she came home with a smile. And in 1961 the happy father had a son ...' Such a fragment of song it was and from whom? It was new and hardly anything is new! And how could something come so strong and sudden so swiftly to snap the sad and slumberous Safeway stupor? Hayes, who rides the discs like Joel McCrea, said, '"1941" , folks.' Oh, yes, he said, '"1941" , by Nilsson.' Nilsson. 'Nilsson' he said, again, and told us it was good, and that was why we smiled, Timothy, we smiled because it was good ...

If one looks past the very '60s references to pink capris and Riviera cars, it is obvious why Nilsson felt so complimented by Taylor's words. It is the best description ever of that timeless feeling, the thrill that comes from hearing a pop song so exciting that it leaps out of the radio and into your long-term memory. Nilsson's "1941" came out in 1967, a year when the airwaves were cluttered with groundbreaking music of every sort. Yet, amid a radio landscape of "new" Dylans and "new" Beatles, Nilsson made an immediate impression upon Taylor and others in the know, because, through his creative magic, he was truly new.

He was born Harry Edward Nilsson III[1] (not "Nelson," as had been reported) on June 15, 1941, Father's Day, in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, New York. Nilsson's best-known quote about Bushwick, a notoriously tough neighborhood, termed it "a crummy place to grow up if you're blonde and white."[2] His father left his mother in 1944, so Harry spent most of his childhood with his mother and his younger half-sister. The family lived in an upstairs apartment at 762 Jefferson Avenue,[3] along with Harry's maternal grandparents[4], two uncles, an aunt and a cousin.

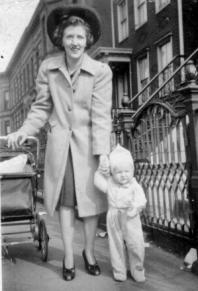

Bette Nilsson and Young Harry

One of his earliest musical influences was his own mother, Bette Nilsson, who wrote two songs which Nilsson later recorded. "She wrote '"Marchin' Down Broadway",'" Nilsson said, "which Irving Berlin offered her a thousand bucks for, I found out. She thought he wanted the whole song, so she said no. He may really have wanted it; I've heard stories about him. Then she wrote '"Little Cowboy".' That was about the extent of her songwriting. I think she wrote poetry at night, you know, and things like that. She once wrote something which she sent to a publisher, called 'I Think I'm Going Mad,' and they sent it back and said, 'So do we!'"

Bette Nilsson and Young Harry

One of his earliest musical influences was his own mother, Bette Nilsson, who wrote two songs which Nilsson later recorded. "She wrote '"Marchin' Down Broadway",'" Nilsson said, "which Irving Berlin offered her a thousand bucks for, I found out. She thought he wanted the whole song, so she said no. He may really have wanted it; I've heard stories about him. Then she wrote '"Little Cowboy".' That was about the extent of her songwriting. I think she wrote poetry at night, you know, and things like that. She once wrote something which she sent to a publisher, called 'I Think I'm Going Mad,' and they sent it back and said, 'So do we!'"

In early 1952, Nilsson, his mother and sister took the long bus ride to San Bernardino, California, home of Bette's brother and his wife, Uncle John and Aunt Anna. They stayed there for a month and then moved to the nearby town of Colton, where they lived in a trailer on the parking lot of the rail-side diner where Nilsson's mother waited tables.

As one might gather by now, Nilsson, despite growing up in the '50s, did not have a Norman Rockwell childhood. He has a total of six stepfathers, and his mother constantly had problems with alcohol and money. In late 1956, Bette moved herself and the children back east, to Long Island, New York, to avoid prosecution for forged and bounced checks. They moved in with Bette's sister and her husband, Aunt Cissy and Uncle Fred, and slept in the family's basement and attic during that cold winter. Nilsson started school there after the new year and became very popular, making the baseball and basketball teams. His teenage life seemed to be achieving some semblance of normalcy.

Nilsson's mother and sister moved out of Fred and Cissy's house in early 1957, but Nilsson stayed there in order to complete the school year. When summer arrived, he was allowed to stay on at the home, provided he use the salary from his job as a caddy to help with household expenses. However, that June, around the time of his 16th birthday, he was fired after getting into a fight while on the job. When his uncle said that he couldn't afford to keep Nilsson on at the house, the dejected teenager decided to hitchhike to Los Angeles, California, and rejoin his mother and sister, who had returned there a month before.

Nilsson returned to L.A. to find that he was on his own. His mother was in jail, presumably having been caught up to her old tricks with bad checks. Nilsson took a job at the Paramount Theatre, which he later recalled was the fourth largest theater in the world. "They used to have live stage shows with all the rock 'n' roll bands, and they had a piano in the basement. So these guys passing though, the Sparrows or something, would show me some chords."

During this same period, Nilsson became taken by the explosion of great rock 'n' roll and R&B; music on the airwaves. "I had this beat-up little radio that I used to listen to late at night. I listened to a guy named Dick Hugg, 'Huggy Boy.' It was an all-black station. He played the Olympics, the Coasters, Ray Charles. He played Ray Charles's 'I've Got A Woman'! When I used to go to sleep, if that song came on the radio, no matter how low the volume, I would hear it, wake up and listen to it and go, 'Yeah!'"

In the summer of 1958, Nilsson took time off from the Paramount and moved back in with his Uncle John and Aunt Anna, the relatives who housed the Nilssons when they first came west in 1952. He worked pumping gas at the station owned by John, who was a mechanic. John also was a major musical influence on Nilsson, teaching him how to sing harmony. During this period, Nilsson started listening to the Everly Brothers and formed a singing duo with his best friend, Jerry Smith. "We were the poor man's ... we were somewhere between the Everly Brothers and Jan and Dean, actually." Nilsson said.

After spending the summer with his Uncle John, Nilsson resumed working at the Paramount. "The theater promoted me to assistant manager and sent me to San Francisco, California, to work at a theater that they owned up there. I worked there for a year and then I came back down to act as temporary manager, to close down the L.A. Paramount Theatre, 'cause they were tearing it down to 'pave paradise and put up a parking lot,'" as Joni Mitchell sang.

"When we closed the Paramount (circa 1960), the cashiers who worked for me were all getting jobs at a bank, and I said, 'Hell, if I'm their boss, I know how to count money, I can reconcile the balance. I'll apply.' So I lied on my application and told them I graduated high school.

"Got a job at the bank. I took some tests, and I came out very high in the computer area. They were just starting computers. They said, 'Do you have any interest in computers?' I said, 'This is a dream come true. You bet!'

"So I got the job, kept the job. They found out I didn't graduate from high school and they called me in to fire me. I said, 'Look, I've done a good job. You know I have. I haven't been late,' and all that stuff. I cried tears and I said, 'Look, I had to do it, otherwise I wouldn't be able to get a job.'

"They really liked me, so they went out on a limb. They said, 'Okay, you're on probation for six months.' So I said, 'All right,' and I worked really hard for the six months, and they just kept me on and eventually I was in charge of the place when I left."

During the early 1960s, Nilsson began to build a career in music. Since he worked the night shift at the bank, his days were free for hanging around music biz offices. With his natural charm, he made many connections just from spending time in waiting rooms and befriending office personnel. The fall of 1960 saw him singing demos for songwriter/producer Scott Turner. According to Nilsson, Turner paid him five dollars for each of the 11 songs (all Turner compositions) that Nilsson recorded. Years later, Turner decided to capitalize on Nilsson's success by releasing the demos (filled out by studio musicians). He telephoned Nilsson to work out payment. Nilsson later claimed to have told Turner, "You already paid me. Five dollars a song. That was our deal." The "album" came out in two different pressings. If this story, as told by Nilsson, is true, then Turner must have made back his 55 dollars many, many times over.

One of the legends surrounding Nilsson is that he never performed any live concerts. He was very proud of the fact that, with all his fame, he remained an amateur (not amateurish) at live performance. While that claim is mostly true (save cameos at Beatlefests and such, plus the specials he did for the BBC), Nilsson, when pressed, admitted having done a show with Jerry Smith. "We did one," he chuckled and corrected himself. "Well, we did half of one. There was an oldies but goodies type show, a road show with all rock 'n' rollers: The Safaris, the Elegants, Don and Dewey. This promoter, Hal Ziger[5] , needed an act to fill in for The Safaris. We said, 'Okay. What do we sing?' He said, 'Whatever the heck you want! It pays 15 dollars. Do you want it?'

One of the legends surrounding Nilsson is that he never performed any live concerts. He was very proud of the fact that, with all his fame, he remained an amateur (not amateurish) at live performance. While that claim is mostly true (save cameos at Beatlefests and such, plus the specials he did for the BBC), Nilsson, when pressed, admitted having done a show with Jerry Smith. "We did one," he chuckled and corrected himself. "Well, we did half of one. There was an oldies but goodies type show, a road show with all rock 'n' rollers: The Safaris, the Elegants, Don and Dewey. This promoter, Hal Ziger[5] , needed an act to fill in for The Safaris. We said, 'Okay. What do we sing?' He said, 'Whatever the heck you want! It pays 15 dollars. Do you want it?'

"So, came the night, we had to be at (a bar at) 35th and Weston, which is a tough area, South Central L.A. We got there at 11 in the morning for some reason. They were still cleaning out the bar. It stunk of whiskey. It was a black bar, in a black neighborhood. Pretty soon the musicians all started showing up, carrying their guitars and cases and everything, and we were scared to death. We didn't know what the hell we had gotten into. Then they said, 'Okay, bus time!' So we get on the bus and the first thing the driver does, he looks back at everybody, then he looks toward us and says, 'Back of the bus!' We were the only white guys there! And everybody cracked up, saying, 'Hey, that's all right, man, you're all right. You can sit here if you want. He's just being friendly, you know.' It was hysterical. We drove to a place right outside of San Diego, California, called National City, to this big auditorium there. It seated about a couple thousand people, and the audience was all black.

"When it was our turn to go on, we went, 'Holy Jesus what have we gotten ourselves into now?' We had bought some blue corduroys and blue sweaters like the Kingston Trio." Nilsson laughed and added, "Alpaca sweaters! And the gig was paying, don't forget, 15 dollars. So we went our onstage, believe it or not, and we walked out and there were howls of laughter. I mean, that place went nuts! We were scared; we'd never done anything like this before anyway, and this was really scary. And I looked at Jerry and he looked at me and we both looked at each other in fear. We didn't look at the audience, just at each other! We sang, 'If I Had A Hammer.'"

Nilsson laughed at the weirdness of it all. "Now, if they had had hammers, they would have killed us! They started laughing, and at the end of it they roared approval. They were screaming and clapping, all in fun. And I said, 'That's it,' and he said, 'That's it. We're outta here.'

"So we got the first bus back to L.A., where we found our Volkswagen trashed," Nilsson said. "So the whole thing cost me a car, the Alpaca sweater, and then, on top of that, I gave a check to Hal Ziger. I said, Here's 10 dollars back. We only did one song. Since I gave him his money back, my amateur status was still intact," Nilsson concluded, chuckling proudly.

In 1963, Nilsson's songwriting and recording career gained steam, thanks largely to his creative partnership with songwriter John Marascalco ("Good Golly Miss Molly"). "John Marascalco deserves a lot of credit," Nilsson observed. "He was the first guy to loan me 300 bucks, and he also took me into the fold to write songs with him."

Together they wrote "Groovy Little Suzie"," which, Nilsson admitted, "sounded exactly like 'Good Golly Miss Molly.'" The similarity must have appealed to Little Richard, for he wound up recording the song. Nilsson recalled that when he sang the song for Richard, the flamboyant star told him, "My, you sing good for a white boy!"

"Groovy Little Suzy" By Little Richard

Marascalco, besides being the first major business person to recognize Nilsson's songwriting talent, also financed Nilsson's first professional recording efforts, a pair of singles released on independent labels. Neither disc made waves, but Nilsson was glad to get the experience. The first one, "Baa Baa Blacksheep," came out on Crusader Records. Since Nilsson did not care to use his real name, he used a joke name based on the "sheep" concept, "Bo Pete."

The record itself came about from a chance meeting between Nilsson and a girl group. "I was in a little studio one day," he said, "hanging around, doing demos, and I heard these teenage girls walk by singing four-part harmony. They called themselves the Beach Girls. They had this quality to them that was so raw and natural, and I thought, 'Ooh, that's cool!' So I was working on '"Baa Baa Blacksheep",' and I said to the girls, 'Here, come here a sec,' and I started to play the song. I said, 'You do the backgrounds, like the Raeletts or something.'" The song garnered a smattering of local airplay, enough to merit a Bo Pete follow-up: Nilsson's own version of "Groovy Little Suzie" coupled with "Do You Wanna (Have Some Fun)" on the Crusader offshoot Try.

One day, Nilsson was hanging around Ziger's office, shooting the breeze with a promoter's secretary, a woman named Sonny, when a breathless music publisher rushed in. As Nilsson later told the story, "He said 'Sonny! Quick! Do you know where I can get a singer? Just someone who could sing this song I'm doing? And I gotta get it over to (Mercury executive) Jack Tracy today.' She said, 'Him.'

"He said, 'Can you sing?' I said, "Well, what have you got?' He played this song called '"Wig Job",' because wigs were getting popular again, flips and all that, you know? 'So there goes my baby with a new lo-ok/Got all the fellows in the neighborhood ho-oked/Wig Job.'

"I said, 'What are you gonna use for the other side?' He said, 'Anything you want.' I said, 'Well, I have this little song I was writing ...' This was before I started writing good songs. It was "Donna I Understand." Recalling it, Nilsson laughed at the silliness of the title. "And the guy at Mercury said, 'I like the singer and I like the song "Donna," but the other side I don't like!'

"So, as a result of that, I got signed by Mercury, and I said (to the song publisher), 'Bye!' They kept me on the label for a year and they didn't put anything out, and finally they put that one single out." Since they thought that "Harry Nilsson " sounded too much like a middle-aged Swedish businessman, the single came out under the name "Johnny Niles."

Throughout Nilsson's early recording career, he kept his night job at the bank. "I worked there every night, from five o'clock 'til about one o'clock. I'd get off around quarter-to-one if I was lucky. I'd race to a bar and fortify myself, and then race back to this office which I was allowed to use because I cleaned the windows for them when they weren't working one night. I washed all the windows and they couldn't believe it. I made the place spic and span. They said, 'Boy! No one's ever done anything like that for us. Here, here's a key.' That was Perry Botkin's office." Perry Botkin was a successful songwriter, arranger and music publisher.

In late 1964, Nilsson hooked up with Phil Spector. It was an interesting meeting of minds; Nilsson, who was just beginning to blossom, and Spector, who was at his artistic and commercial peak. Nilsson was recording a demo at Gold Star, which was also Spector's studio of choice. "Phil was walking down the hallway and he heard my demo and he said, 'Who's that?' Turns out that Perry Botkin used to publish Phil when Phil was a teenager, and he said, 'That's Harry Nilsson .' Phil said, 'That's a good song. Did he write it?' Perry said, 'Yeah, well, he and I wrote it,'" Nilsson said.

Nilssonny and Cher

The next thing Nilsson knew, the First Tycoon of Teen phoned him to suggest that they meet, and the two started to write together. The pairing resulted in three songs: "This Could Be the Night," recorded by the Modern Folk Quartet, and the Ronettes numbers "Paradise" and "Here I Sit"." As Nilsson recalled, the latter tune's lyrics presaged Nilsson's later toilet-humor songs such as Son of Schmilsson's "I'd Rather Be Dead"; "It was taken from a men's room wall: 'Here I sit, broken hearted/Fell in love, but now we parted' instead of 'farted.' 'Couldn't see the writing on the wall' If that isn't enough of a hint! I did a record with Cher and Phil, "A Love Like Yours." I called us Nilssonny and Cher!"

Nilssonny and Cher

The next thing Nilsson knew, the First Tycoon of Teen phoned him to suggest that they meet, and the two started to write together. The pairing resulted in three songs: "This Could Be the Night," recorded by the Modern Folk Quartet, and the Ronettes numbers "Paradise" and "Here I Sit"." As Nilsson recalled, the latter tune's lyrics presaged Nilsson's later toilet-humor songs such as Son of Schmilsson's "I'd Rather Be Dead"; "It was taken from a men's room wall: 'Here I sit, broken hearted/Fell in love, but now we parted' instead of 'farted.' 'Couldn't see the writing on the wall' If that isn't enough of a hint! I did a record with Cher and Phil, "A Love Like Yours." I called us Nilssonny and Cher!"

Spector, for reasons best known to him, chose not to release the MFQ's "This Could Be the Night" at the time. (It can now be heard on the Spector boxed set, Back to Mono.) The classic pop song became legendary in L.A. pop circles and a particular favorite of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson, who has reportedly made attempts at recording it over the years. ("This Could Be the Night" has the rare distinction of being in Wilson's permanent memory. In March of this year, during his appearance at New York's Algonquin Hotel, he was unable to recall some of his own songs, but acceded enthusiastically to a request for that Nilsson tune.)

Near the end of 1964, Nilsson's Mercury contract ran out, and he was picked up by Tower, a new arm of Capitol Records. "I had T-1; the first contract ever signed on Tower," Nilsson claimed. Unfortunately, Tower, like Mercury, quickly forgot about its new signee. "The kept me under wraps for a year and didn't do anything, so I said, 'Please let me get out of this contract. You're not recording me. Get me out.' So, finally, we had one session. The reason we got that was, George Tipton put up his life's savings, 2,500 bucks, and we recorded four tracks and we sold them to Tower." Tipton, who went on to become a highly-rated arranger, was then a music copyist in Perry Botkin's office. Reflecting upon Tipton's investment in his career, Nilsson said, "That's what I call belief. He took that money and he paid for the session, which he arranged, his first arrangement."

"Tower also bought some other demos by the New Salvation Singers, which was the group that another guy in Botkin's office had, and I sang along with the group for free." Nilsson noted that Tower later reissued those recordings to capitalize upon the fame that he had acquired as a hit songwriter. "Suddenly, because I had a hit song as Harry Nilsson , the group became credited as 'Harry Nilsson and the New Salvation Singers!'"

During this period, Nilsson supplanted his bank income by recording commercial jingles. His voice was heard on commercials for Ban Deodorant ("Ban won't wear off as the day wears on") and Red Roof Inns; (an Elvis-style "Look for the Red Roof")[6], among others. He also recorded a song that was used in an episode of the popular TV show I Spy.

Ban Deodorant Commercial

Like most other songwriters of the mid '60s, Nilsson changed his writing style in the wake of the Beatles' success. However, with Nilsson it was not just a case of emulating the Fab Four purposefully. In fact, when he first heard them, he was filled with jealousy. Fortunately, by the time The Beatles released Rubber Soul, Nilsson had learned to stop worrying and love the Fabs. Something about the group struck a very special chord within him, as though they were his kindred spirits. Their sheer creativity inspired him to stretch his own artistic boundaries.

Nilsson continued to spend his after-work hours in Perry Botkin's office, writing songs. "I remember one magical day," he recalled with a hint of wonder, "I wrote three songs in one night: "Without Her," "1941," and "Don't Leave Me" in one night. And I realized then that I would never write another bad song.

"The next day, they came into the office and I said, 'Listen to what I did last night.' I had put the songs on tape. They said, 'You wrote those last night?' They guy from across the hall had a publishing company, and he said, 'I'd like to buy that one, "Without Her," for $10,000.' They sold it to him, thinking they had made a big bundle, and then they had all these other songs of mine, so it was great. Then Glen Campbell recorded "Without Her" and they heard about it first, so they said to the guy across the hall, 'We'll give you your 10 grand back.' They gave it back, plus five. They put the song back in their catalog and then sold the catalog for $150,000!

"The guy across the hall had insisted that I do a demo on "Without Her" an octave down and never go for the high notes because, he said, no one could sing those. I said, 'You're crazy. I just sang it.' He said, 'You can, but you can't show that to an artist who can't hit those notes.' As a result, Glen Campbell heard the version with the lower notes and he sang it down there."

Nilsson soon became a "happening" songwriter, and his tunes were picked up by everyone from Jack Jones to Billy J. Kramer, Sandie Shaw to Fred Astaire, and Herb Alpert to George Burns. Artists began to chart with his songs, including the Yardbirds with "Ten Little Indians" and Canadian folk-punk singer Tom Northcott with the excellent Leon Russell-produced "1941."

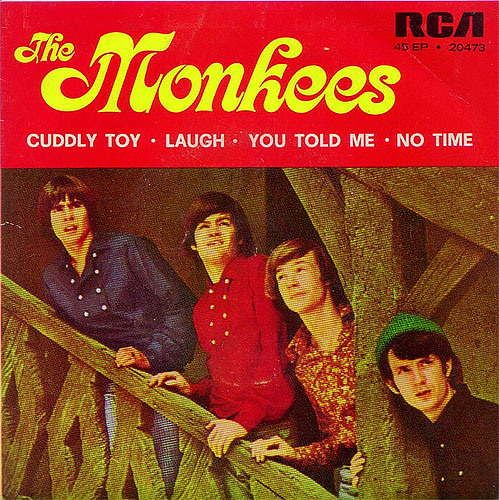

Around the beginning of 1967, Nilsson ran into an old friend, Chip Douglas of the Modern Folk Quartet, at the Los Angeles, California, industry hangout Martoni's. "I said, 'Hi, Chip! What are you doing?' 'I'm producing these guys.' I said, 'I'm sorry, who are these guys?' He said, 'These are the Monkees.' I had heard all the publicity about them, but I didn't know what they looked like. I said, 'Oh, fantastic!' They were doing their first or second album. Chip said to the Monkees, "Harry is a fantastic writer. I would like to take him into the studio and let you hear a couple of tunes of his.' I said, 'Sure, I'd love to.' He said, 'Would you come over now?' I said, 'Yeah, I'd love it.' Especially because I'd heard rumors that they were going at four million record sales out of the box.

Harry Nilsson's Monkees Demos

"So I sang seven, eight or nine songs, and Michael Nesmith said, 'Man, where the fuck did you come from? You just sat down there and blew our minds like that. We've been looking for songs, and you just sat down and played an album for us. Shit! Goddammit!' He threw something on the floor. And he went and got Micky Dolenz and he said to him, 'Would you listen to this man? Listen to that!' Micky gave a surprised laugh, and Davy Jones started laughing over one song, and it was like the three of them were just out of their tree. Only Peter Tork couldn't give a shit."

The first Nilsson song that the Monkees released was "Cuddly Toy" , which they recorded in April, 1967, and released seven months later on their album Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.. By the time the song came out, loyal viewers already knew it from the Monkees' TV show. On the show, the super-cuddly Davy Jones commonly sang the tune to a sweet teenage lass. Viewers in the know laughed at such an innocent display, confident that "Cuddly Toy" was really about that less-than-romantic experience known as the "gang bang." When Goldmine asked about this, Nilsson laughed guiltily. "Well, it crossed my mind. I would try to think of something that would mean something else as well as its intended meaning, and I would use the most twisted version I could think of."

The first Nilsson song that the Monkees released was "Cuddly Toy" , which they recorded in April, 1967, and released seven months later on their album Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.. By the time the song came out, loyal viewers already knew it from the Monkees' TV show. On the show, the super-cuddly Davy Jones commonly sang the tune to a sweet teenage lass. Viewers in the know laughed at such an innocent display, confident that "Cuddly Toy" was really about that less-than-romantic experience known as the "gang bang." When Goldmine asked about this, Nilsson laughed guiltily. "Well, it crossed my mind. I would try to think of something that would mean something else as well as its intended meaning, and I would use the most twisted version I could think of."

Although popular wisdom has it that Nilsson was signed to RCA in the wake of the Monkees' recording "Cuddly Toy" , Nilsson's first recording session for the label was in February of 1967, two months before the Monkees recorded his song. Nilsson commonly warned journalists not to assume anything about him, but it seems safe to assume that RCA caught the buzz created by Perry Botkin's office, which happened to be on the same floor as the label.

The story goes that RCA signed Nilsson to a $75,000 contract, but Nilsson's side of the story was that they signed him for "zero." Although the truth may be in between, Nilsson's figure sounds probable, since in February, 1967, he was still, commercially if not artistically, an untested property.[7]

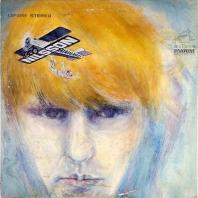

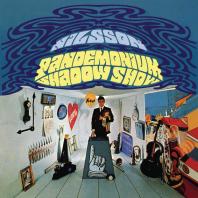

Pandemonium Shadow Show

The title of Nilsson's first album, the October, 1967, release Pandemonium Shadow Show, was taken from the book Something Wicked This Way Comes, by one of his favorite authors, Ray Bradbury. Legend has it that Nilsson originally wanted to title the album after the book itself, but legal considerations prevented his doing so. (It is also hard to imagine RCA getting worked up over the idea.)

Pandemonium Shadow Show

The title of Nilsson's first album, the October, 1967, release Pandemonium Shadow Show, was taken from the book Something Wicked This Way Comes, by one of his favorite authors, Ray Bradbury. Legend has it that Nilsson originally wanted to title the album after the book itself, but legal considerations prevented his doing so. (It is also hard to imagine RCA getting worked up over the idea.)

In spite of Nilsson's previous recordings for Mercury, Tower and smaller labels, he considered Pandemonium Shadow Show his true debut. It is not hard to see why. For one thing, it was the first record of his to make the most of his three octaves-plus voice. Many listeners, particularly those in the industry (who were practically the only ones who heard the album at its time of release) were stunned by the way that the multi-tracked Nilsson could make himself sound like anything from a gospel choir to the bigger-than-God Beatles. In addition, unlike Nilsson's previous efforts, which were tailored for the disposable pop market, Pandemonium Shadow Show had an odd feel, contemporary, yet timeless. Such praise may sound like hype, but one listen to the album shows that, with such songs as "Without Her," "1941," and "Cuddly Toy," it sounds startlingly fresh.

Although Pandemonium Shadow Show missed the charts, it was received enthusiastically by critics and others in the know. One person who fit into both categories was past and future Beatles press agent and music columnist Derek Taylor. As Taylor would later relate in his liner notes to Nilsson's second album, Aerial Ballet, he was so thrilled with Pandemonium Shadow Show that he ordered up an entire box of LPs so that he could turn others on to his new discovery.

As 1968 rolled around, the biggest development in Nilsson's business life was that he had finally gotten the courage to quit his job at the bank. He was in his tiny office at RCA when he learned of the Apple press conference that made him, at least temporarily, a household world. "It was the second largest press conference since World War II," Nilsson recalled. "They asked the Beatles, 'Who is your favorite American artist?' John said, 'Nilsson.' And a few seconds later some guy asked Paul, 'Who is your favorite American group?' and Paul said, 'Nilsson.' Then there was a hubbub throughout the room: 'Nilsson' 'Oh, yeah, the group from Sweden.' Nobody knew what it was."

It was at this time that Nilsson made his famous decision not to perform. "The phone started jumping off the hook. They called RCA to say, 'I'd like to talk to someone about Harry Nilsson .' And RCA would ring them to my phone. I had asked for an office in my contract, because I was used to being in an office, you know? And I said, 'Hello?' 'Yeah, this is Tony Green. I'm from the NME,' or something. He said, 'I'd like some information about Nilsson.' And I said, 'Yeah?' 'Can you tell me where he's appearing?' I said, 'I'm not.' 'Oh, is this Nilsson? Oh! Uh, sorry! Listen, I just called because we're doing an article on you and we're trying to find out more about you. You've only had one album out?' I said, 'Yeah.' He said, 'Where are you playing?' I said, 'I'm not.' This is just after I left the bank! He said, 'Oh, uh, well, where did you play last?' I said, 'I haven't.' Then he said, 'Well, where are you planning to play next? What's your next gig?' I said, 'I don't have any plans.' He said, 'Oh, Where did you play last?' I said, 'I haven't!'

"He said, 'You've never performed?' And I said, 'No. My amateur status is still intact, thank you.' And the guy went ... you could hear him! ... each one of these callers about the same press conference, they all went, 'Whoop!' And I thought, 'Ah! Mystique! This is good. I'm the guy who doesn't perform. Good! Leave it in!' Like the one-name joke. That was [producer] Rick Jarrard's idea, because 'Harry' sounded like, you know, 'Harry'. At the time, there were 18 television commercials like, 'Haaarry, take out the gaaarbage!' Rick said, 'Harry's a funny name. It's so New York. "Haarry," it's a drone name.' So anyone who asked about my performing, I would answer the same way: 'I'm not, I haven't, I don't.' They'd say, 'Why is that?' I said, 'Um, I don't know.' And sometimes I'd say, 'I'm doing something the Beatles can't have done.' 'What's that?' 'Not perform,'" Nilsson said.

There is another story, which Nilsson also told writers, which places the Beatles' admiration for Nilsson at an earlier date than the Apple press conference. Since this story conflicts directly with the Apple story, and since there are only a handful of people alive who know exactly what took place, one hopes that an accurate chronology will someday surface. Story #2 has it that Derek Taylor first heard Nilsson in the spring or summer of 1967, before Pandemonium Shadow Show was even released. He brought demos of the album to Nat Weiss at the Beatles's management company, NEMS. Nilsson was introduced to George Harrison (then staying on Los Angeles, California's Blue Jay Way) as NEMS attempted to seduce the singer away from RCA. According to this story, Nilsson was slow to decide. As soon as he made his mind up to say "yes," Beatles manager Brian Epstein died, and the offer ended as NEMS fell into disarray.

Not long before or after the Apple press conference, Nilsson got an unexpected phone call on Monday morning at seven. As he later told Rolling Stone, the call began like this:

"Is this Harry? This is John."

"John who?"

"John Lennon."

"Huh?"

"This record [Pandemonium Shadow Show] is fuckin' fantastic, man. I just wanted to say you're great."

After exchanging a few more pleasantries, the two said goodbye. The next Monday morning at seven, Paul McCartney called, also to rave about the album. Nilsson later claimed that he got all dressed up the following Monday morning and waited by the phone, expecting, in vain, that Ringo Starr would call.

A few months later, Derek Taylor invited Nilsson to fly over to London to attend some of the Beatles's recording sessions. Nilsson sat in on what became known as the White Album sessions and spent some quality time with John Lennon. He played Lennon his just-released second album, Aerial Ballet, from which Lennon especially liked "Mr. Richland's Favorite Song" (named after record promoter Tony Richland). Recalling those times with Lennon, Nilsson told Rolling Stone, "I really fell in love with him. I knew he was all those things you wanted somebody to be."

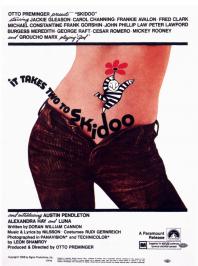

Skidoo

At the time that Nilsson visited the Beatles, he was working on the soundtrack to the Otto Preminger movie Skidoo. Released at the end of 1968, the film was a bizarre attempt at psychedelic extravagance, with an all-star cast that was mostly well-over 30: Jackie Gleason, Carol Channing, Groucho Marx (in his last screen appearance), Burgess Meredith, and Peter Lawford, among others. Nilsson wrote the entire score, including background music and pop numbers. Most unusually, in a cinematic first, he sang the entire closing credits. Although the film was recently revived to an enthusiastic audience at New York's prestigious Film Forum, it has never attained more than a small cult following. As critics David Ehrenstein and Bill Reed wrote in their book, Rock on Film, "They weren't ready for it in 1968, and they still aren't."

Skidoo

At the time that Nilsson visited the Beatles, he was working on the soundtrack to the Otto Preminger movie Skidoo. Released at the end of 1968, the film was a bizarre attempt at psychedelic extravagance, with an all-star cast that was mostly well-over 30: Jackie Gleason, Carol Channing, Groucho Marx (in his last screen appearance), Burgess Meredith, and Peter Lawford, among others. Nilsson wrote the entire score, including background music and pop numbers. Most unusually, in a cinematic first, he sang the entire closing credits. Although the film was recently revived to an enthusiastic audience at New York's prestigious Film Forum, it has never attained more than a small cult following. As critics David Ehrenstein and Bill Reed wrote in their book, Rock on Film, "They weren't ready for it in 1968, and they still aren't."

Nilsson himself made a cameo appearance in Skidoo as a prison "Tower Guard" on LSD. Since he had never taken acid, he played the role as though he were drunk. An astute viewer will catch him doing a quick Stan Laurel shrug.

Nilsson's Aerial Ballet

Nilsson began recording Aerial Ballet (named after his grandparents' turn-of-the-century trapeze act) [8] before Pandemonium Shadow Show even came out. One of the songs he chose for the album was the Fred Neil tune "Everybody's Talkin'" which he recorded in November, 1967. Nearly one year later, when Aerial Ballet came out, RCA released "Everybody's Talkin'" as a single. While it made plenty of noise on regional charts, even reaching #51 in Record World, the single's time had not yet come. It slipped by Billboard's Hot 100, despite five weeks of "bubbling under."

Nilsson's Aerial Ballet

Nilsson began recording Aerial Ballet (named after his grandparents' turn-of-the-century trapeze act) [8] before Pandemonium Shadow Show even came out. One of the songs he chose for the album was the Fred Neil tune "Everybody's Talkin'" which he recorded in November, 1967. Nearly one year later, when Aerial Ballet came out, RCA released "Everybody's Talkin'" as a single. While it made plenty of noise on regional charts, even reaching #51 in Record World, the single's time had not yet come. It slipped by Billboard's Hot 100, despite five weeks of "bubbling under."

Aerial Ballet began with "Good Old Desk," a song which, like "Cuddly Toy," was much misinterpreted. Once again, the source for the misinterpretation was Nilsson himself. "After I wrote the song," he told Goldmine, "somebody asked me what it was about and I said, 'I don't know.' Then I realized what the initials were." Viewers of the television show "Playboy After Dark" witnessed Nilsson tell Hugh Hefner, with a straight face, that the song's meaning was in its initials ... "God." Nilsson admitted to Goldmine, "I bullshitted him. I thought it was funny. Nobody else thought it was funny!" Meanwhile, the catchy melody of "Good Old Desk" was not lost on English popsters The Move, whose songwriter Roy Wood lifted its bridge for his song, "Blackberry Way" which became the group's only U.K. #1 hit.

Nilsson was very embarrassed at the mention of his 1960s television appearances, which included spots on German television and on the U.S. sitcom "The Ghost and Mrs. Muir." Referring to the latter show, Nilsson later explained to the British press, "I was advised to have a manager, so that year (1968) I had one. He suggested I accept the part. So I just went on and did what they told me. It was awful!"

Nilsson's best contribution to '60s television was "Best Friend" , the theme he wrote and sang for "The Courtship of Eddie's Father." Considering that it was one of his best-known songs, it is surprising that Nilsson never put it on record. The reasons for its non-release are probably due, at least in part, to legal and technical considerations. The recording of "Best Friend" used on the TV show was owned by the show's producers and not by Nilsson or RCA. Since the song was written as a theme and not as a commercial tune, it is short; its only verses are the ones heard on the show. In Nilsson's later years, he was impressed by the song's lasting popularity, and he attempted to re-record it for his final, unreleased album. (At the time of his last interview, he had not yet re-recorded it to his satisfaction.)

According to legend, it was Nilsson's inexhaustible booster Derek Taylor who helped him get this next break by playing Aerial Ballet for director John Schlesinger, who as auditioning music for the film Midnight Cowboy. When the word was out that Schlesinger needed songs, responses came from everyone from Joni Mitchell to Bob Dylan ("Lay Lady Lay"), to Randy Newman (reportedly, "Cowboy" ). Nilsson himself hoped for his own composition "I Guess the Lord Must Be in New York City," but Schlesinger's final choice was Nilsson's version of "Everybody's Talkin'".

When it came out as a single off of the soundtrack in August, 1969, one year after it had "bubbled under" and nearly two years after it was recorded, the world finally heard L.A.'s best-kept secret. An international smash, "Everybody's Talkin'" reached #6 on Billboard's Hot 100. The Midnight Cowboy soundtrack spurred by the single's success, sold over one million copies and stayed on the Top 200 for 57 weeks. The following March, "Everybody's Talkin'" won Nilsson his first Grammy, for "Best Contemporary Vocal Performance, Male."

Even before "Everybody's Talkin'" hit, 1969 was a banner year for Nilsson. That March, Three Dog Night hit #55 with the Aerial Ballet song, "One." A million-seller, "One" was a breakthrough for both the group and the songwriter.

Nilsson's third album, Harry, followed close on the heels of Midnight Cowboy. It spawned a Top 40 single, "I Guess the Lord Must Be in New York City," proving that the song originally written as a movie theme could succeed on its own. Although Harry did not include "Everybody's Talkin'" (fans would have to buy Midnight Cowboy or Aerial Ballet for that), it became Nilsson's first hit album, reaching #120 during its 15 weeks on the charts. It came at an important time for Nilsson, for it showed "Everybody's Talkin'" listeners, who had been attracted by his singing voice, that he had a unique songwriting voice as well.

Nilsson later noted that his album catalog tended toward trilogies. There is a point to that (no pun intended), for Harry seems in many ways like the final chapter in the trilogy that began with Pandemonium Shadow Show. Its songs are linked by a theme of retrospection, from the haunting "Mournin' Glory Story" (which Nilsson later admitted was unwittingly influenced by the Beatles' "For No One"), to the wistfully childlike "The Puppy Song" (originally written for Mary Hopkin). In addition to ending a cycle, the album also began one, with Nilsson's first of many great Randy Newman covers, "Simon Smith and the Amazing Dancing Bear."

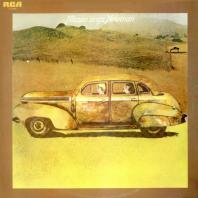

Nilsson Sings Newman

Nilsson followed Harry with a project close to his heart, Nilsson Sings Newman. Released in February 1970, the album stands apart from the rest of Nilsson's catalog, or anyone's catalog, for that matter. Its uniqueness comes from the fact that it is a true meeting of minds, each one of them a great songwriter and artist.

Nilsson Sings Newman

Nilsson followed Harry with a project close to his heart, Nilsson Sings Newman. Released in February 1970, the album stands apart from the rest of Nilsson's catalog, or anyone's catalog, for that matter. Its uniqueness comes from the fact that it is a true meeting of minds, each one of them a great songwriter and artist.

By 1970 Randy Newman was well-known in industry circles, with one solo album to his credit as well as many songs recorded by others, but commercially he was an unproven quantity. It would not be until the end of that year, after Nilsson Sings Newman came and went, that Newman would have his first major hit song in the United States, Three Dog Night's version of "Mama Told Me Not To Come." It was a daring move of Nilsson's to record an entire album of Newman's songs, and one which ultimately widened the audience for Newman's music. Although Nilsson Sings Newman did not chart, it was lauded by the press, earning more than one citation for "Album Of The Year."

Nilsson Sings Newman is centered upon Newman's songs, Nilsson's voice, and Newman's own piano work. In some ways it is more a Newman album than a Nilsson album, because the delicate arrangements make the songs the star. Nilsson's own style was particularly compatible with Newman's. Listening to this album, and especially comparing it with Newman's own versions of the songs, the respect Nilsson felt for Newman is strongly evident. Nilsson's own personality comes through in the vocal arrangements. As with the previous albums, all the background voices, from the "female soul singer" to the "barbershop quartet," belong to Nilsson. On songs such as "Love Story," he created the perfect blend of romance and irony, qualities which are very present in Nilsson's own songs.

Nilsson later recalled how much effort went into that collaboration, as well as how tedious things got for his partner: "Randy was tired of the album when we were finishing making it, because for him it was just doing piano and voice, piano and voice, over and over and over. But I needed that practice because I needed to learn the songs inside and out the way that he knew them, but do it my way so that it (stylistically) matched both of us. Once I got the take down, I knew what I was going to do with it later. He didn't."

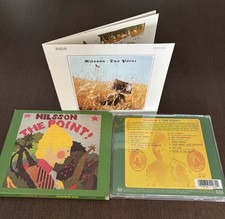

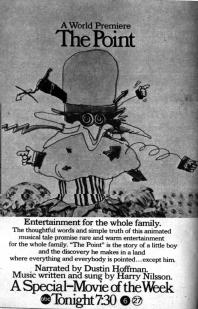

The Point! Ad

Nilsson spent much of 1970 working to bring another pet program into fruition, an animated musical TV special, aimed at children of all ages, called "The Point!." He was inspired by the idea that everything was pointed. Well, it seemed profound to him at the time, as he later explained: "I was on acid and I looked at the trees and I realized that they all came to points, and the little branches came to points, and the houses came to point. I thought, 'Oh! Everything has a point, and if it doesn't, then there's a point to it.'" Kids, don't try this at home.

The Point! Ad

Nilsson spent much of 1970 working to bring another pet program into fruition, an animated musical TV special, aimed at children of all ages, called "The Point!." He was inspired by the idea that everything was pointed. Well, it seemed profound to him at the time, as he later explained: "I was on acid and I looked at the trees and I realized that they all came to points, and the little branches came to points, and the houses came to point. I thought, 'Oh! Everything has a point, and if it doesn't, then there's a point to it.'" Kids, don't try this at home.

Broadcast in early 1971, with story and songs by Nilsson and narration by Dustin Hoffman, The Point! was a cross-generational hit, just as Nilsson had hoped. The soundtrack album, which was narrated by Nilsson, reached #25 during a 32-week chart life and launched the Top 40 hit "Me and My Arrow."

Nilsson knew that, with his current success, fans would search for his first two albums, and he wasn't pleased. After completing The Point!, and before beginning his next new album, he returned to the studio to tinker with his old tapes. The result was June 1971's Aerial Pandemonium Ballet, a collection of remixed and retooled versions of tracks from Pandemonium Shadow Show and Aerial Ballet. Although the new versions mostly retained the feel of the originals, Nilsson added some creative twists, such as a canny allusion to "One" in the tale of a star's fall from grace, "Mr. Richland's Favorite Song." Included on the album was a retooled version of "Daddy's Song," a tune which was originally included on Aerial Ballet but was yanked from it when RCA feared competition for the Monkees' version. Although Aerial Pandemonium Ballet was no smash, it sold better than either of the albums it compiled, reaching #149 on the Top 200.

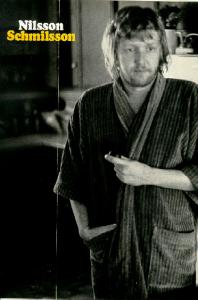

Nilsson Schmilsson Ad

In June, 1971, Nilsson went back into the recording studio after a year long absence to make the album that would become his all-time best seller, Nilsson Schmilsson. The album, Nilsson's first album of mostly original, non-soundtrack material in the two years since Harry, was done at Trident Studios, London, England, with a producer who was new for Nilsson, Richard Perry. From its hilariously homey cover photo to its tongue-in-cheek title, Nilsson Schmilsson was a surprising change from Nilsson's previous records.

Nilsson Schmilsson Ad

In June, 1971, Nilsson went back into the recording studio after a year long absence to make the album that would become his all-time best seller, Nilsson Schmilsson. The album, Nilsson's first album of mostly original, non-soundtrack material in the two years since Harry, was done at Trident Studios, London, England, with a producer who was new for Nilsson, Richard Perry. From its hilariously homey cover photo to its tongue-in-cheek title, Nilsson Schmilsson was a surprising change from Nilsson's previous records.

The greatest surprise was that Nilsson had made such a great artistic leap. Nilsson later observed, "I really needed it, too. That was exactly what I was hoping would happen. That album was a great meeting [of minds] ... I was so glad to meet Richard Perry, because he was thinking the same thing I was thinking at the same time: now let's go to work and do some rock 'n' roll and get down!"

It was while in England that Nilsson heard and recorded the Badfinger song "Without You." While the Badfinger version (on their 1970 album No Dice) stands on its own, there is no question that Nilsson's version was the definitive one. The emotional centerpiece of Nilsson Schmilsson, "Without You" deserved all its success. It topped the U.S. charts for four weeks and the U.K. Charts for five, selling well over one million copies and earning Nilsson his second Grammy.

Nilsson Schmilsson spent nearly one year on the charts, reaching #3, going gold, and spawning two more hit singles, both penned by Nilsson: "Jump into the Fire" and "Coconut." The hard-rocking "Jump into the Fire," which today would be called "alternative," was a completely left-field choice for a follow-up to "Without You." Fortunately, fans took it on its own merit and sent it up to #27. To this day, it is the only hit to feature a bass detuning. Nilsson, who later presented with the contrast between "Jump into the Fire" and his earlier work, answered, "My earlier stuff had the same soul in it, only it was more subtle."

Nilsson Schmilsson was still on the charts in July 1972 when the artist released his next album, Son of Schmilsson. RCA chose the single "Joy" to coincide with the release, not a wise move, as "Coconut" was still in the Top 40 and, moreover, "Joy" was not the most commercial song on the album. (It wasn't the least commercial one either; that honor forever goes to "You're Breaking My Heart.") The single missed the charts entirely. Fortunately, the label realized its mistake and quickly spun off the poppier tune "Spaceman."

The only Son of Schmilsson song to hit the Top 40, "Spaceman" reached #23. The follow-up, "Remember (Christmas)." was a minor hit that winter, edging up to #53. Son of Schmilsson was a profitable album for Nilsson it hit #12, spent 31 weeks on the chart, and went gold ... but there was something about it that put off buyers who had been drawn to Nilsson by "Without You."

That something had to do with Nilsson's heavy use of both bathroom and bedroom humor, often within the same song. Although finding reasons why records do or don't sell is a largely futile pursuit, it is safe to say that one song in particular, "You're Breaking My Heart," dispelled the romantic image that Nilsson had created of himself. Today, the song sounds almost quaint, but in those pre-punk days of 1972, when pop lyrics rarely got racier than Melanie's "Brand New Key," many buyers were forever put off by Nilsson's enthusiastic use of the f-word.

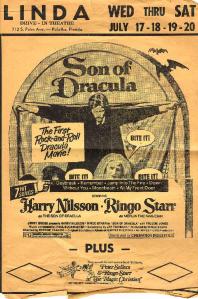

Son of Dracula Ad

In late 1972, Ringo Starr, who was by then a close pal of Nilsson, invited him to play the title role in a campy horror movie that Starr would produce, Son of Dracula. When the film came out, most assumed that Starr got the idea from Nilsson's vampirish album cover for Son of Schmilsson, but the truth was even spookier: Starr got the idea for the film before he even saw Nilsson's album.

Son of Dracula Ad

In late 1972, Ringo Starr, who was by then a close pal of Nilsson, invited him to play the title role in a campy horror movie that Starr would produce, Son of Dracula. When the film came out, most assumed that Starr got the idea from Nilsson's vampirish album cover for Son of Schmilsson, but the truth was even spookier: Starr got the idea for the film before he even saw Nilsson's album.

Since Nilsson was doing most of his recording in London, and since so many of his friends were there, he bought a flat on Curzon Place, in fashionable Mayfair. Throughout the '70s, the flat served him well, but more than once, when he lent it out to friends, it became the site of tragedy. Mama Cass died in his bed there, in July of 1974. Four years later, legendary Who drummer and close Nilsson pal, Keith Moon died there as well, in the same bed. Fortunately for Nilsson, Pete Townshend was kind enough to buy the place from him after Moon's death so that Nilsson would never have to see the flat, or the bed, again.

Although Nilsson claimed not to believe in jinxes, he told Goldmine that his London flat had bad vibes from the start. "It was just a typical London flat, but it was in a great neighborhood. It was across from the Playboy Club, diagonally. From one balcony you could read the time from Big Ben, and from the other balcony you could watch the bunnies go up and down.

"Robin Cruikshank was Ringo's partner at the time, and he did interior decorations, furniture and stuff. I said to Robin, 'Just do whatever kind of decorating you want to do with it. I'll sign a blank check, you fill it in. Have you ever had a dream design you wanted to do? Use this place, 'cause I'm only going to be using it six months out of the year.' So I came back to London six months later and it was all done. There was a ribbon on the door there to welcome me, they had fresh fruit in the fridge. I looked around and I said, 'This is incredible.' This flat had felt wallpaper ... bright, royal blue with yellow, red and green felt stripes. It was like, 'Wow! Where am I?' It was all steel, chrome and glass. Everything was purchased for the space."

"I went to check out the bathroom, and there was a beautiful glass tub with a design of scenery of trees and bushes cut in. But then there were two sinks and two mirrors. I looked into one and there was a picture of an apple tree, and the other one was a hangman's noose. I called Ringo and said, 'I don't think this is too funny. Do you mind?' He said, 'What?' I said, 'The hangman's noose in the bathroom.' He said, 'What? Hold on a second ... Joan, have someone go over to Harry's place and put up something else ... Don't worry, Harry, I didn't even know about it. Robin must have done it.' So I said, 'Thanks,' and he sent over a nice apple tree mirror to take its place. But ever since that day something struck me. It's like whistling in the graveyard, but ... then, when Mama Cass died, it was, like, wow. Then when Keith Moon died ... Those phone calls (notifying me) were devastating, you know?"

In March 1973, while planning got underway for Son of Dracula, Nilsson recorded an album as different from Son of Schmilsson as champagne is from Ripple: A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night. As with the transitions from Harry to Nilsson Sings Newman, he once again followed a hit album with one that was a labor of love. It started when Nilsson approached his friend Derek Taylor about doing an album of standards. Taylor suggested bringing in arranger Gordon Jenkins, a living legend best known for his work with Frank Sinatra. With Taylor producing and a 26-piece orchestra backing, Nilsson recorded the songs which he had always loved, from Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson's "Makin' Whoopee" to Bob Cole and Rosamond Johnson's "Lazy Moon." The latter song was Nilsson's favorite of the album, as it had been sung previously by his idol Oliver Hardy. (In fact, the album's cover featured Nilsson reprising the thumb-as-lighter gag from the Laurel and Hardy classic Way Out West).

Even for those who knew Nilsson's earlier albums, A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night was a stunner. It succeeded on a multitude of fronts: as a document of the best music of a bygone era, as a work of art (of Jenkins's witty-yet-delicate arrangements), and, perhaps most importantly in to listeners, as the ultimate makeout album. The first album of Nilsson's to contain no vocal harmonies, it let his voice stand alone as an instrument worthy of interpreting the work of Tin Pan Alley's greatest writers. Derek Taylor, in his liner notes, reiterated his claim that Nilsson was "the best contemporary singer in the world." The album's greatness dared listeners to disagree.

Released in the summer of 1973, A Little Touch of Schmilsson in the Night only managed to make it to #46 during its 17-week U.S. chart run. It fared better in the U.K., where it made #20. RCA released one single, "As Time Goes By," which crawled up to #86 on the Hot 100. Today, in light of such successful albums of the '80s and '90s as Linda Ronstadt's What's New, Annie Lennox's Diva and the Sleepless in Seattle soundtrack (which popularized Jimmy Durante's version of "As Time Goes By"), it is obvious that Nilsson was ahead of this time.

Son of Dracula disappeared as soon as it saw daylight in the summer of 1974. The soundtrack, featuring Nilsson songs and dialogue from the film, fared slightly better, reaching #160 and spinning off a Top 40 single, "Daybreak." The song would be the last hit of Nilsson's lifetime.

Around the beginning of 1974, Nilsson renewed his friendship with John Lennon, who was in Los Angeles, California, recording with Phil Spector for what would become the album Rock And Roll. Lennon had recently separated from Yoko Ono and taken up with May Pang, and the period of drinking and debauchery that ensued became known as his "lost weekend."

The most famous incident from this period was that notorious night at the Troubadour, a L.A. club which was packed with celebrities and fans there to see the Smothers Brothers comeback. Among those celebrities were Lennon and Nilsson, and they were too drunk to care about who the audience was there to see. They were dying to be noticed; Lennon even sported a tampon on his head. What they did and said has been described elsewhere and is largely unprintable here (for example, Lennon told a Smothers Brother to intercourse a bovine creature). The upshot, which made headlines worldwide, was that the man with a tampon for a hat and the man with the voice that was like Modess[9], "soft as a fleecy cloud," were ejected from the premises.

Nilsson later complained to Rolling Stone, "that incident ruined my reputation for 10 years. Get one Beatle drunk and look what happens!" Even in his last interview, he was defensive: "It still haunts me. People think I'm an asshole and a mean guy. They still think I'm a rowdy bum from the '70s who happened to get drunk with John Lennon, that's all. I drank because they did. I just introduced John and Ringo to Brandy Alexanders, that was my problem.

"(My association with) John Lennon hurt me a lot, with the bad press. But on the other hand, I owe John everything. I had signed an agreement with RCA for a new, $5 million contract and they had reneged on it; the new president didn't sign it. I had been saying, "The contract's binding. We'll take you to fucking court, man.' And the president had said, 'It's not binding here.' And there was this question of jurisdiction and all that stuff, and I was prepared for a fight.

"I said to John, 'I just got $5 million, and they took it away from me, like that.' He said, 'Ah, they're all fuckers, Harry. They're all fuckers." He said, "Just go down and tell the guy he's a fucker.'

"So I went down to RCA. We'd been up all night long and it was now 10 in the morning. Both still drunk, with shades, hats, dark jackets. The secretary said, 'Mr. Glancy,[10] uh, Harry Nilsson and John Lennon are here to see you, sir.'

"What?' Boom! Door opens immediately. We walk in. There we are, you know? In every office, heads are turning to look at us. He said to John, 'Hi! How are you doing, sir? Would you like a cigar?' John said, 'No, thanks. I'd take a brandy.' So we had a brandy, and John said, 'Look, it's about Harry. You know, you've only ever had two artists on your label: Elvis Presely and Harry. He told me what you're paying him. Look, for that money, I'll sign it. You've got an artist! Pay the two dollars!" "Pay the two dollars' was like saying, pay the parking ticket, rather than fight City Hall. He said, 'I'll sign with you, for that kind of money.'

"When the guy heard that, his mind went 'Bing!' Dollar signs! So he said, 'Well, we'll have to get the contracts together.' I said, 'No, no. They're on the 10th floor. They're in Legal. Ask Dick Etlinger, in Business Affairs. He's the guy.' So he calls up and says, 'Do you have the Nilsson contract? Could you bring it up here?' Because he didn't want to look like an asshole in front of John.

"They brought up the contract. I said, 'All you have to do is affix your signature where it says "President." Just write your name on it.' He said, 'Okay,' and he did it, right in front of John. John made me $5 million that minute. I looked at John for a minute and I almost cried. Then I said, 'I'd like four copies.' I gave one to John, one to me, one in the hotel safe, and I sent one out to California. An that's how I got to be a multimillionaire. Thank you very much, John!"

Lennon decided to produce Nilsson's next album, and Nilsson, not surprisingly, was all for it. The result was the underrated Pussy Cats, released in August 1974. (RCA rejected Lennon and Nilsson's original title, Strange Pussies.) Listening to tracks such as the Jimmy Cliff cover, "Many Rivers to Cross," it is easy to understand why so many fans were cross, for Nilsson literally lost his voice during the recording sessions. Although one of his vocal cords was ruptured and bleeding, Nilsson refused to let on just how much pain he was in, fearing that John would stop the sessions. As a result, the album's booze-drenched, gut-wrenched feel is closer to that of the post-punk efforts of the Replacements or Alex Chilton than it is to anything else by Nilsson. It reached #60 on the Top 200, aided no doubt by the prominent placing of Lennon's name on the cover.

By the time of Nilsson's next album, 1975's Duit on Mon Dei, Nilsson's voice had returned, although it occasionally took him some effort to bypass its rough edges, Nilsson's original title for the album, which RCA rejected at the last minute, was the tongue-in-cheek God's Greatest Hits. Duit on Mon Dei, and the album that followed, Sandman (1976), seemed as though they were part of the trilogy that started with Pussy Cats. Unfortunately, as far as the public was concerned, any similarity between the three was purely coincidental. Neither album broke the upper half of the Top 200. Nilsson was justifiably angry, as he told Goldmine, "I'm getting pissed off because three of my best albums ... Duit on Mon Dei, Sandman, and Pussy Cats ... got totally overlooked. And yet there are songs on there that I wish I wrote. Well, I did!"

Nilsson's next album, ...That's the Way It Is (1976), was his most blatantly commercial effort to date, composed mainly of covers of oldies and newies. It seemed a little strained, but still had some classic Nilsson moments, particularly his version of Randy Newman's "Sail Away." The album fared poorly, reaching #158 during six weeks on the Top 200, but Nilsson had a major success that year in the British stage production of "The Point!" starring the Monkees's Micky Dolenz and Davy Jones, "The Point!" ran at London's Mermaid Theatre and was well received, spawning an original cast album.

Knnillssonn

The 1977 album Knnillssonn (pronounced "Nilsson") was Nilsson's last for RCA and, in his opinion, his best. All-original, it was his most consistent rock album since Nilsson Schmilsson. By this point, Nilsson's happy marriage to his third wife, Una Nilsson, had caused him to cut down on the partying. As a result, Knnillssonn is extremely well-thought out, from its Agatha Christie-influenced "Who Done It?" (no relation to "Ten Little Indians") to Nilsson's most beautiful love song in years, "All I Think About is You."

Knnillssonn

The 1977 album Knnillssonn (pronounced "Nilsson") was Nilsson's last for RCA and, in his opinion, his best. All-original, it was his most consistent rock album since Nilsson Schmilsson. By this point, Nilsson's happy marriage to his third wife, Una Nilsson, had caused him to cut down on the partying. As a result, Knnillssonn is extremely well-thought out, from its Agatha Christie-influenced "Who Done It?" (no relation to "Ten Little Indians") to Nilsson's most beautiful love song in years, "All I Think About is You."

When Knnillssonn came out, RCA assured Nilsson that it would receive the kind of heavy promotion befitting such a hit worthy album. That was in July. The next month, Elvis Presley died. Another label might have been able to promote a current artist's album and milk a dead superstar's catalog at the same time. Unfortunately, RCA was not another label. Knnillssonn did do better than all Nilsson's other records since Pussy Cats, reaching #108 on a 10-week chart stay, but that was not good enough for Nilsson, who began looking for a way out of his contract.

January 1978 saw RCA release the soundtrack to the Gene Wilder film The World's Greatest Lover, featuring the Nilsson vocal "Ain't It Kinda Wonderful." A few months later, someone at the label, unbeknownst to Nilsson, decided to fill in the gap between the artist's albums. The resulting compilation, Greatest Hits, was a factor in Nilsson's decision to leave the label.

When Goldmine brought up Greatest Hits, handing Nilsson the album's cover, he could not contain his fury. "Look at this. This is RCA for you," he said. The front cover photograph is the back of a man, presumably Nilsson, looking at his reflection in the mirror. The back cover is the same man's face, holding the mirror so that it covers nearly all his features. "That's not me." Nilsson fumed. "Now, do you think RCA has got any fucking soul whatsoever, when they do shit like this? I begged them in the very beginning, "Don't ever put out a best-of album until I'm dead or I'm off the label.' And, no, they sneak this out and don't tell me about it, and hire a guy to look like me, and then they took and old picture of me and reversed it and put it in the mirror. How about that for trash?" Ironically, Greatest Hits was Nilsson's last Top 200 album, hitting #140 in a five-week chart stay.

Zapata

Although Nilsson did not release any records in 1979 (perhaps because he was working out his release from RCA), he was busy working with old friend Perry Botkin on a new musical, "Zapata!" The show opened the following year at the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut, but failed to move on to Broadway. Nineteen seventy-nine also saw director Robert Altman commission Nilsson to write the songs for the movie Popeye. The soundtrack, released in December 1980, featured the film's stars, rather than Nilsson himself, singing Nilsson's tunes. Nilsson did record his own demos of the songs, tapes of which reportedly exist.

Zapata

Although Nilsson did not release any records in 1979 (perhaps because he was working out his release from RCA), he was busy working with old friend Perry Botkin on a new musical, "Zapata!" The show opened the following year at the Goodspeed Opera House in East Haddam, Connecticut, but failed to move on to Broadway. Nineteen seventy-nine also saw director Robert Altman commission Nilsson to write the songs for the movie Popeye. The soundtrack, released in December 1980, featured the film's stars, rather than Nilsson himself, singing Nilsson's tunes. Nilsson did record his own demos of the songs, tapes of which reportedly exist.

In 1980, Nilsson signed to Mercury Records and released one album, Flash Harry, which was available in Europe and Japan but not in the United States. His only album released under the full name "Harry Nilsson," it is his rarest work and also his least appreciated. Although Flash Harry had its merits, it left reasonable doubt as to whether Nilsson could still successfully stretch his talent to album's length.

The fact was that Nilsson, after Flash Harry, was no longer interested in making albums anyway. Rock 'n' roll would always be a part of his life, but his family needed him and he wanted to, in the words of his friend Ringo's album title, "stop and smell the roses." Thus began one of the most active rock "retirements" since David Bowie called it quits.

Testimony of Harry Nilsson before the United States House of Representatives

The death of Nilsson's beloved friend John Lennon inspired him to, for the first time in his career, use his celebrity to draw attention to a cause. He not only joined the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, but became its most active and prominent spokesman. He used every available platform to broadcast the message of gun control, from Beatle fan conventions to the halls of Congress. In his last interview, he spoke passionately about the cause. "The world is full of fear," he noted. "I wasn't aware of how much fear there was, until this last couple of years ... that the world is on the brink of chaos. Every human being at any given moment can go mad. And that's one of the reasons we've got to get rid of the handguns. I think that the President should write an executive order declaring a national state of emergency ... 24,000 handgun deaths every year ... and actually, physically, ban handguns. Give everybody six months to turn them in. When they do they get a tax credit. The remaining handguns are to be collected ... all registered guns, period.

Testimony of Harry Nilsson before the United States House of Representatives

The death of Nilsson's beloved friend John Lennon inspired him to, for the first time in his career, use his celebrity to draw attention to a cause. He not only joined the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, but became its most active and prominent spokesman. He used every available platform to broadcast the message of gun control, from Beatle fan conventions to the halls of Congress. In his last interview, he spoke passionately about the cause. "The world is full of fear," he noted. "I wasn't aware of how much fear there was, until this last couple of years ... that the world is on the brink of chaos. Every human being at any given moment can go mad. And that's one of the reasons we've got to get rid of the handguns. I think that the President should write an executive order declaring a national state of emergency ... 24,000 handgun deaths every year ... and actually, physically, ban handguns. Give everybody six months to turn them in. When they do they get a tax credit. The remaining handguns are to be collected ... all registered guns, period.

"Now, that will leave only the bad guys with the guns, but now we will know who to identify. You have the right to self-defense, but you don't have the right to carry arms if you're not in the militia. The Second Amendment says, "A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state" - well, we have that. It's called the National Guard, established in 1912. So if you want a gun, join the National Guard and you'll get to shoot their guns. Another alternative is, if you have a gun then you must keep it at the gun store and only use it for target range shooting."

Hawkeye Entertainment Business Card

In the early '80s, Nilsson, after loving movies all his life, ventured into the production field. He formed Hawkeye Entertainment with legendary writer Terry Southern (Candy), and they had moderate success with several projects, most notably the Whoopi Goldberg vehicle The Telephone. On the musical front, although he was officially "retired," he could no more avoid musical involvement than Elizabeth Taylor could avoid marital involvement. Among his many projects, he helped write and produce songs on [Ringo Starr's album Stop and Smell the Roses and himself recorded songs for compilation albums and soundtracks.

Hawkeye Entertainment Business Card

In the early '80s, Nilsson, after loving movies all his life, ventured into the production field. He formed Hawkeye Entertainment with legendary writer Terry Southern (Candy), and they had moderate success with several projects, most notably the Whoopi Goldberg vehicle The Telephone. On the musical front, although he was officially "retired," he could no more avoid musical involvement than Elizabeth Taylor could avoid marital involvement. Among his many projects, he helped write and produce songs on [Ringo Starr's album Stop and Smell the Roses and himself recorded songs for compilation albums and soundtracks.

As the '90s rolled around, Nilsson began to seriously consider making a new album. The idea came from necessity, as all of Nilsson's RCA money had been stolen by an unscrupulous financial adviser (who was convicted and sent to prison). By that time, along with wife Una, he had six children at home, plus he had an independent son from his previous marriage. In addition he was diagnosed with diabetes and related ailments, and became increasingly aware of his own mortality.

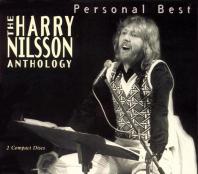

An unwelcome turning point occurred on Valentine's Day, 1993, when Nilsson suffered a massive heart attack. After he survived miraculously, he started writing and recording in earnest, hoping for a hit that would secure his family's financial future. He also lobbied RCA to release a three-disc compilation of his work. Nilsson took the time to sequence the projected discs, and came up with a fitting title: Personal Best.

At the time of the Goldmine interview, RCA was insistent upon a two-disc set, and was not receptive to Nilsson's track sequence or his title. The label's seeming indifference to Nilsson's wishes hurt him deeply. "They don't understand," he said, sounding pained. "I only have three albums left in me, period. This is the twilight of my career. I have one shot left. That's to do this album I'm doing ... and two more, hopefully ... and this (three-disc) compilation to explain who I am to the listening public, because they've never put it all together. This is my opportunity to put it all together, the way I sequenced it. My list. Schindler's list. And I'm telling you, it breaks my heart, and it's already 20 percent dead, okay? It's breaking my heart, to have to go through this nonsense. I went through this when I was a boy, I went through this when I was a man, with RCA doing things like that. Just once, I would like them just to bend. One time. One time!"

Personal Best

A few days after the interview, this writer spoke with Nilsson by telephone, for the last time. Nilsson said that he had decided not to fight RCA's wishes for a two-disc set, and he was working on trimming down his proposed three-disc track sequence to make up for the change. He hoped that the label would accept his new sequence, and the Personal Best moniker. He sounded less bitter and more upbeat, speaking enthusiastically of the autobiography which he started. Two days later, on January 15, 1994, after completing the vocal tracks for a new album, he died of a heart attack.

Personal Best